Peak Historical Ignorance

Trump's neocolonial designs on Greenland, Venezuela and other countries resurrect a dark, dumb past.

As the Trump administration renewed its threats against Greenland and other U.S. neighbors following the Venezuela invasion, my former L.A. Times colleague Josh Gohlke wrote this essay on America’s imperial past and the president’s weaponization of a revisionist history to justify a radical rejection of the postwar order. Josh, a veteran opinion editor and writer who resigned from the Times for ethical reasons last year, posts frequently about politics and policy on his Substack, Laughing Leads to Crying.

Talk to you later.

It’s easy to forget underneath the mountain of absurdities Donald Trump has amassed in less than a year, but one of his first acts of this term was to reattach William McKinley’s name to the nation’s highest peak, which had been re-recognized by its Alaska Native name, Denali. This was an expression not just of Trump’s familiar racism and nostalgia but also of his avowed fondness for the 25th president.

Trump’s bad taste in presidents — Andrew Jackson; himself — is well-known, but his preoccupation with one so obscure and middling revealed that the supposedly “great” American past of his rhetoric is not so much the 20th century of his youth as the 19th. His reckless invasion of Venezuela and menacing of our other hemispheric neighbors — Greenland, Mexico, Cuba, Colombia — amount to a wholesale rejection of postwar progress and a revival of a past characterized by great-powers colonialism, of which McKinley was an American avatar.

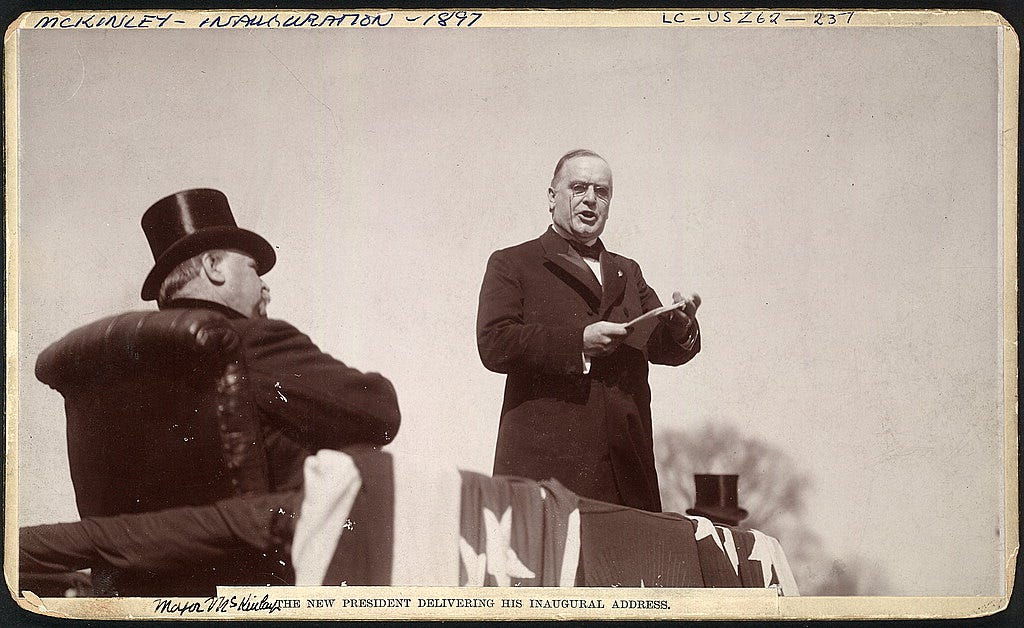

Trump’s adherence to another 19th-century relic, protectionism, is his most obvious connection to McKinley: According to his questionable historical analysis, McKinley “made our country very rich through tariffs and through talent” as “a natural businessman” (something, having spent his career in politics, law and the military, he was not in any respect). But Trump’s Day One defenestration of Denali approvingly emphasized McKinley’s imperialism first and foremost, asserting that he “heroically led our Nation to victory in the Spanish-American War” and an “expansion of territorial gains.”

This proclamation — and its grim realization as a matter of foreign policy over the past week — is, even for Trump, an astonishing reversal of reality. The McKinley presidency, which began in 1897, was the high-water mark of the United States’ belated, benighted entry into the colonial era, including our acquisition of the Philippines, Guam, American Samoa, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and, briefly, Cuba. The notion that this period was anything other than a disaster has been brutally repudiated by more than a century of history.

The United States is still grappling with the consequences of its colonialism. One hundred twenty-eight years after McKinley presided over the forcible seizure of Puerto Rico from Spain, for instance, the island remains a U.S. territory with more people than 18 states, triple the nation’s poverty rate and no federal representation.

And the repercussions of American imperialism are of course dwarfed by those of Europe’s, of which the United States itself is one result and Greenland is a remnant. One measure of the duration and breadth of European conquest is that Norse settlement of Greenland dates to the first millennium; the huge, icy island has been claimed as a colony by Denmark (originally the united kingdom of Denmark-Norway) since before the American Revolution. The Danes have granted the territory increasing autonomy since World War II, however, culminating with a 2008 referendum that gave Greenlanders expanded home rule, a measure of control over foreign relations and a right to hold a vote for full independence.

Trump, until very recently a self-styled antiwar isolationist, now threatens to forcibly revert Greenland’s status to unreconstructed colonialism under a nation forged in high-minded opposition and bloody resistance to that very notion. Why? Probably, judging by his acknowledged fixation on Venezuelan oil and riches in general, for plunder, but also, by his own account, “for national protection.”

That’s funny, because the United States has enjoyed unfettered military access to the island since World War II, when Denmark was occupied by Nazi Germany and the United States took Greenland in defense. A 1951 agreement between Denmark and the United States allows the latter to expand its military presence there at will, and the postwar NATO alliance, of which both nations are founding members, obligates us to defend each other.

The United States is famously the only country to have invoked this provision: After 9/11, more than 18,000 Danish troops were deployed to Afghanistan, and 33 were killed in action. For a country that is not quite as populous as Maryland, that’s comparable to a loss of nearly 2,000 Americans.

The deadly seriousness of this international alliance — one the Trump administration muses of demolishing as frivolously as it did much of the White House — speaks to another ill of the colonial era. Great powers, as it turns out, don’t reliably agree on who gets to be great and how far their greatness extends, leading to relatively constant conflict culminating in, you know, the whole world war problem. As if to underscore the renewed risk of such a catastrophe, the U.S. Coast Guard seized a Russian-flagged tanker carrying Venezuelan oil this week, and Trump called for increasing the world’s biggest military budget by more than half, to $1.5 trillion.

In stark contrast, the postwar order led by the United States accorded this country and its globe-spanning military, economic and other allies vastly more power, prosperity and peace than the war-torn world it succeeded. It’s why Trump grew up in a country so free, rich and generous — at least to people like him — that even he avoided completely blowing his father’s fortune. Now he would trade the U.S.-led order that enabled such wealth for the privilege of needlessly alienating a staunch ally and subjugating a defenseless neighbor with about half as many residents as Peoria, Ill.

To live through the Trump era is to endure the mind-numbing relitigation of any number of well-settled questions: the value of the rule of law, the trouble with bigotry, the benefits of vaccination and so on. The present reconsideration of colonialism easily ranks among the dumbest.

As it happens, even McKinley, who barely lived to see the dawn of the 20th century, was in some respects a reluctant and accidental colonialist. While his better-remembered vice president, Teddy Roosevelt — who assumed the presidency after McKinley’s 1901 assassination by an anarchist — was a notoriously enthusiastic imperialist, McKinley did not charge into hostilities with Spain. Under pressure from the dissolution of the Spanish Empire in the Caribbean, public and political opinion in favor of Cuban rebels, and trumped-up press coverage of the sinking of the USS Maine off Cuba, he called for an inquiry into the battleship’s destruction and ultimately sought authorization to intervene from Congress, which went on to declare war.

“We want no wars of conquest; we must avoid the temptation of territorial aggression,” McKinley had warned in his first inaugural address. “War should never be entered upon until every agency of peace has failed; peace is preferable to war in almost every contingency.”

How far we have come, though not forward, to arrive at Trump’s act of neo-imperial aggression without so much as briefing Congress, let alone seeking its permission; to his aide Stephen Miller’s frothing that “we live in a world … that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power” — as if all three were one and the same, and as if he had any idea what he was talking about. Somehow a president from the century before last could see farther ahead than this one.

Trump is a total ignoramus when it comes to history.

Thank you for this great essay, Mr. Gohlke.