DOJ’s Vanishing Credibility

New filing in Comey case is Shamefully Deceptive

Up to now, the dominant storyline of the misbegotten federal prosecution of Jim Comey has been the series of tragicomic blunders by the team led by Lindsey Halligan — a complete amateur thrust into a job she was plainly not prepared to perform. The case, corrupt and threadbare in its conception, has been beset by a series of procedural missteps, unforced errors, and increasingly surreal screwups. And Halligan apparently has had no adult supervision to explain to her which way is up, since no prosecutor in the office that she ostensibly leads has been willing to attach their name to the rancid case.

But after this last week, the Keystone Cops storyline no longer goes far enough. The case has now put the credibility of the Department itself to the test. It has flunked spectacularly, putting the rot at the Department’s core on full display.

The Department’s squirrelly conduct in its most high-profile case can only add to the burgeoning sense among federal judges that courts can no longer take DOJ’s representations at face value. We are witnessing a week-by-week erosion of trust — the previous coin of the realm for the DOJ — with sorry consequences for the Department and the public as a whole.

The dramatic highlight of the litigation last week was the gobsmacking revelation that, by Halligan’s own account, the full Grand Jury never voted on the indictment DOJ actually filed. Instead — and this was the revelation that caused shock ripples to radiate through the courtroom and Judge Nachmanoff to go silent in apparent pain for a few seconds — the U.S. Attorney’s Office apparently just cut-and-pasted the 3-count version to make a new 2-count document, which Halligan signed and then handed up to the Court.

This was a serious error. Under Rule 6(f) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, a grand jury may indict only if at least twelve jurors vote to approve the indictment. Courts — including the very case Nachmanoff raised from the bench — have repeatedly explained that an indictment is “found” only when twelve or more grand jurors vote to approve that specific charging document. Nothing in law or logic permits prosecutors to unilaterally revise a proposed indictment after the vote and then treat the new version as valid.

Besides stunning the spectators, the surprise disclosure caused Comey’s attorney Michael Dreeben to leap to his feet and argue a whole new basis for dismissal, namely: “There is no indictment in this case.”

At that instant, the case ceased being primarily about James Comey. It became a case about the Department of Justice.

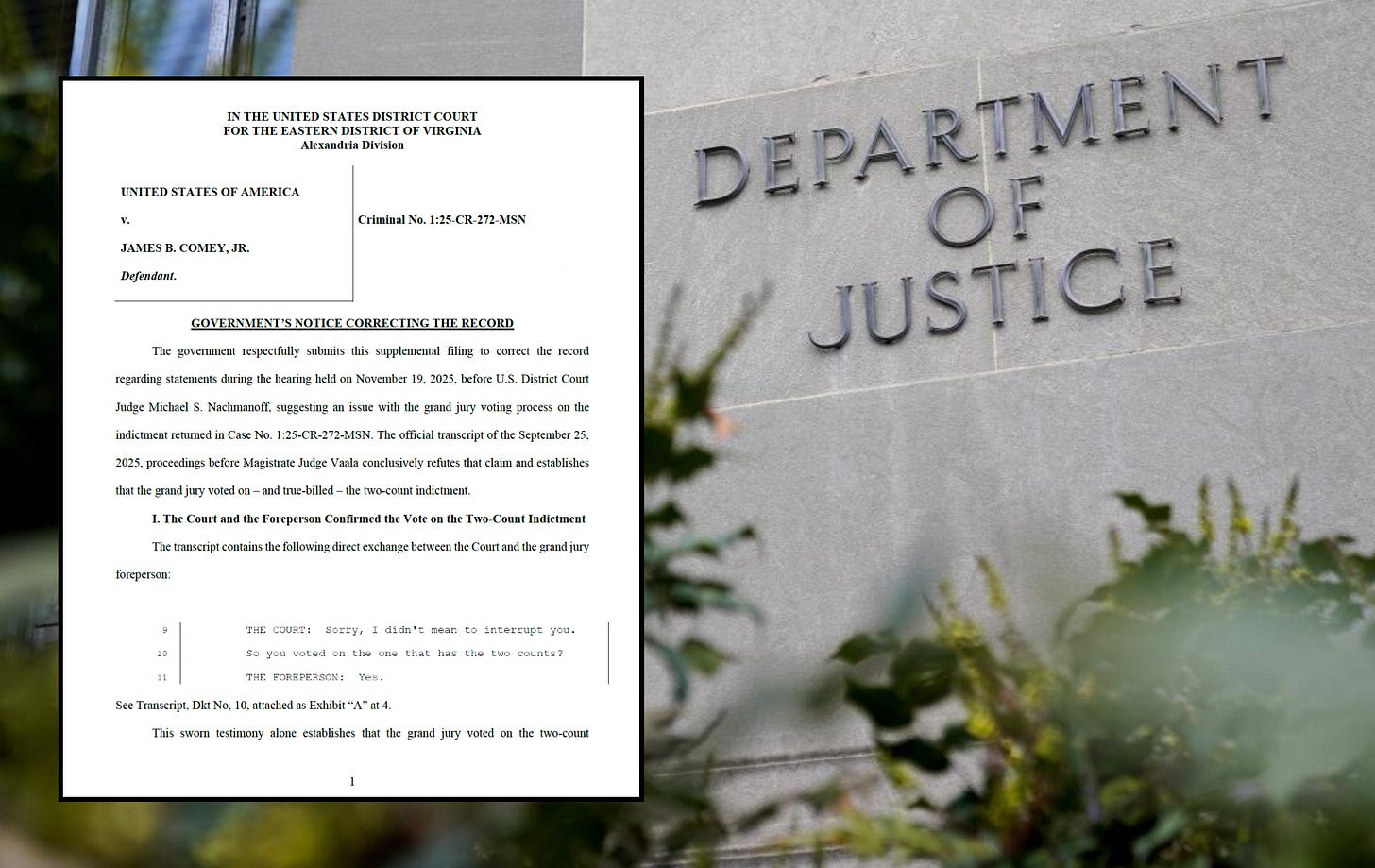

The next day, after an onslaught of negative coverage of Halligan’s admission dominated the news cycle, the Department filed a document that would seem from its title — “Government’s Notice Correcting The Record” — to be designed to clean up its mess.

The filing is probably the most squirrelly, obfuscatory document I have ever seen from the Department of Justice.

On the surface, the Department seemed to be setting out a re-reversal of its position, arguing that whatever bombshell Halligan had dropped the previous day, in fact and on the record, “the grand jury voted on the two-count indictment.”

In reality, the Department wasn’t correcting the record but attempting to reconstrue it. Relying on the words of the clearly confused foreperson, it pushed Nachmanoff to adopt as an authoritative fact that the grand jury did vote on the two-count operative indictment.

But it’s apparent from a careful reading of the record and the government’s slippery filing that the grand jury voted not twice but once — on the 3-count indictment — and the U.S. Attorney’s Office altered that document to produce the version that is in the file. The facts leave room for no other conclusion.

The Department didn’t try to re-explain the mysterious gaps in the record — for starters, the absence of sufficient time to run the new indictment by the grand jury, a court reporter’s account showing that the full grand jury could not possibly have approved the operative 2-count indictment, or the record establishing that the jury was released after deliberations on the first indictment.

The ultimate tell in the Department’s motion is its assertion near the end that the evidence “confirms the Court’s recognition that the two-count true bill is the valid, operative indictment.” But that’s not the question. The pivotal point is whether the grand jury voted separately on that two-count bill.

The motion concluded with a specious claim that the transcript “leaves no room for ambiguity,” even as the motion itself introduced ambiguity through omission, truncation, and rhetorical sleight of hand.

Confronting the government’s legal labyrinth, the Comey response motion plays it straight by stating: “The government has now offered conflicting accounts, but the best reading of the record is that the government never presented a new two-count indictment to the grand jury for a vote.”

The failure to present the revised indictment to the grand jury is a violation of Rule 6 and the Due Process Clause. That doesn’t mean that the error requires a dismissal with prejudice: that additional step is what Comey is arguing in his new motion on Friday, invoking a litany of other misconduct, in particular Halligan’s stunning material misstatements of law to the grand jury.

That legal point, however, is now subsumed by the Department’s tendentious, dishonest motion “correcting the record.” This was not a correction. It was an attempt to pull the wool over the court’s eyes, and about a point that already had been front and center at the hearing.

In the tawdry last eight months, the Trump Administration has repeatedly advanced in court partial accounts, obfuscations, half-truths, and, on occasion, flat-out misstatements.

The first warning shot was the government’s series of shifting responses after sending Kilmar Abrego Garcia to El Salvador in defiance of court orders forbidding his removal. For anyone who thought those were rookie mistakes by a new hyper-political crew, the subsequent months have shown otherwise.

Just this last week — in fact, all on one day — no fewer than three federal judges upbraided the Department and assailed its trustworthiness in scathing terms.

First, Paula Xinis wrote that DOJ’s conduct was “in defiance of my order.” Then, Judge Stephanie Gallagher noted her “grave concerns about the government’s apparent willingness to patch up or disregard this Court’s orders.” Finally, Judge Sara Ellis leveled the scathing criticism: “[i]t becomes difficult, if not impossible, to believe almost anything that [U.S. Government] Defendants represent.”

These sorts of shots across the bow from federal judges are not normal. They document a massive loss of institutional credibility, driven by the DOJ’s lawyering in its signature cases under Bondi.

A powerful new empirical survey published in Just Security last week catalogued the near-collapse of DOJ’s institutional credibility. It identified over 60 cases in recent months in which courts have expressed distrust of government representations, 26 instances of failing to follow court orders, and 68 findings of arbitrary or capricious government action.

The Just Security authors’ conclusion is stark: “Trust that had been earned over generations has been lost in weeks. High deference is out; trust but verify is in.”

The dishonesty in the Comey case is a brazen outlier even by those standards. After the debacle at Wednesday’s hearing, a “notice correcting the record” had to be 100% accurate down to the comma. Instead, at a moment when the court was already confused, irritated, and wary, Halligan and company returned to the DOJ, assessed the damage, and decided to meet a moment of embarrassment with obfuscation rather than transparency. Nachmanoff is certain to see through it. He will not be pleased.

It might be tempting to cabin the Comey fiasco as a discrete mess caused by an overmatched prosecutor. But the damage reaches deeper. DOJ’s credibility is not merely reputational; it is structural — a functional component of the constitutional system — and it is now eroding in ways that scholars are documenting in real time.

Prosecutorial candor is not just a professional virtue and ethical requirement. It is a democratic safeguard. When prosecutors shade facts, elide context, or treat judges as adversaries, they do more than damage a single case. They chip away at the presumption of regularity that allows courts to function and the public to trust the system.

And this case, initiated at the personal insistence of the President and entrusted to political loyalists, demanded extreme professionalism. Instead, it revealed a department under strain — and a leadership cohort willing to cut legal and ethical corners to please the President.

Judge Nachmanoff may or may not dismiss the indictment; the law allows room for either conclusion. But whatever he does, his decision will land at a moment when DOJ’s credibility is under historic strain. The judiciary’s patience is wearing thin .

Credibility takes generations to build and weeks to lose. The Bondi-era DOJ is squandering a storehouse of trust that once insulated the federal justice system. Rebuilding it may take a generation — if it can be rebuilt at all.

That is the precipice the Department is now standing on. And unless it reverses course with urgency and honesty, which seems patently unlikely with the current leadership, the Comey case won’t be remembered for what it tried to prosecute — but for what it revealed about the institution that brought it.

Talk to you later.

We are discovering judges with lifetime appointments are the last defense of democracy and justice. So far it has been judges with regard for justice and law that have held the line. Unfortunately the weak link has proven to be the Supreme Court.

"[W]illing to cut legal and ethical corners to please the President" is a huge understatement! They are willing to lie, elide, & write a whole new novel to please the President. Remembering the fall-out from the last trump debacle, every lawyer involved is looking straight into the gorgon's face of disbarment. Are they so blinded by the cult that they cannot see this staring them down?!